Content Warning

This post discusses suicidal ideation.

Spoiler Warning

This post mentions several early plot points regarding MR. MONK’S LAST CASE. It also details the ending of Agatha Christie’s CURTAIN.

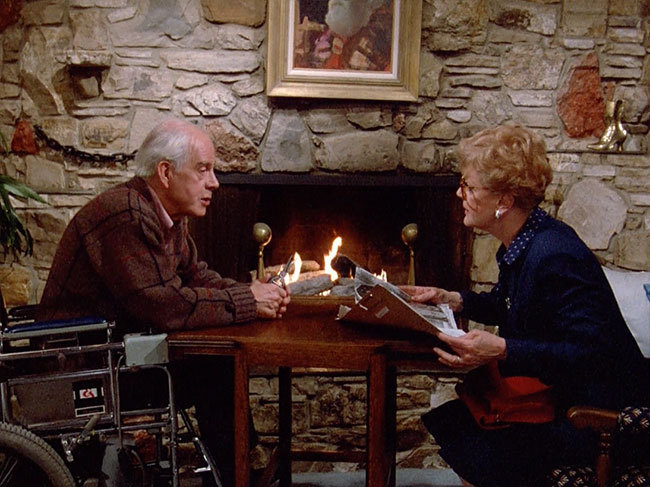

MONK was a USA network TV procedural featuring the very nuanced Tony Shalhoub as Adrian Monk. Monk is a brilliant, married San Francisco detective who struggles with obsessive–compulsive disorder.

In the opening episode Trudy, an accomplished journalist and Monk’s wife, is murdered via a car bomb and Monk finds himself confronting what he sees as an unsolvable case which flares his OCD to unsociable levels. He leaves the force and holes himself up in his apartment, fastidiously dusting and wiping and fussing over his living space, attempting to enact order, at least until SFPD comes knocking at his door and pull him back into the real world.

“It’s a jungle out there.

Disorder and confusion everywhere.”

MONK certainly falls in the realm of cozy, non-threatening murder mysteries. There is no omnipresent sense of dread and little in the way of heightened emotions. However, unlike many other cozy murder mysteries, the heart of the show is its melancholy. Adrian Monk is haunted by his wife’s death for years and burdened by his many compulsions and fears. Shalhoub never plays Monk overly serious or nihilistic but instead portrays him as a petulant man-youth with a bit of hurt behind his eyes.

“No one seems to care; well I do! Hey who’s in charge here?”

The series finale let Monk solve Trudy’s murder, allowing him to move on with his life, to live with answers instead of questions. At least, that was the goal.

14 Years Later…

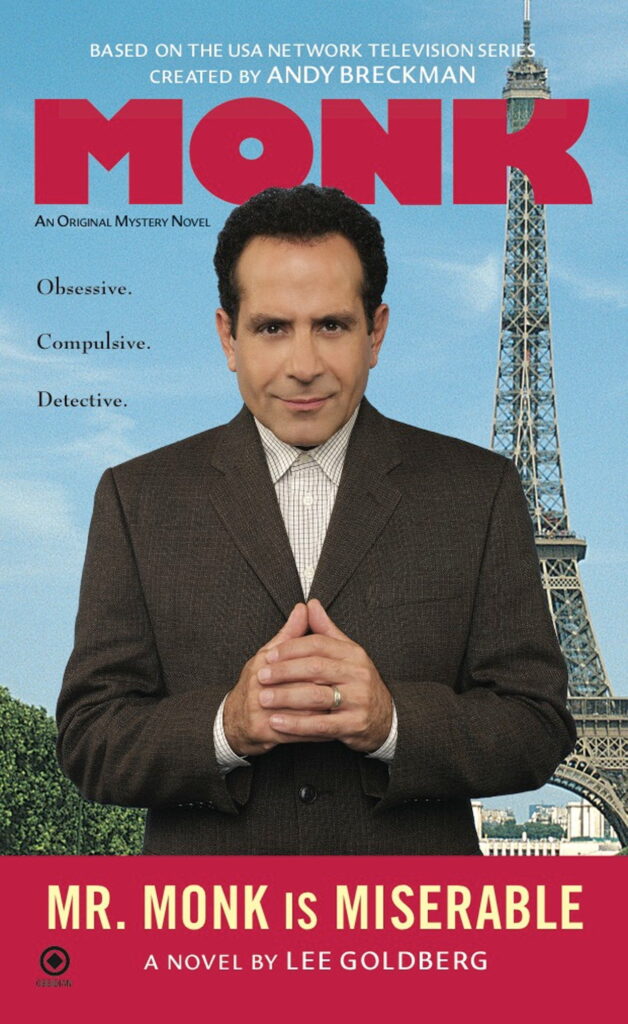

From out of nowhere — and at no one’s request — we have MR. MONK’S LAST CASE. Monk is no longer a consultant for the SFPD. He’s been working on a memoir of his cases which is deemed uncommercial thanks to being overly verbose and concerned with anything but his cases. He’s off of — and stockpiling — his meds, flaring up his OCD.

I will not spoil anything about the case apart from stating that why it pulls a reluctant Monk back into detective mode is surprisingly cruel, especially for a show like MONK but, as it’s a full-blown made-for-TV film, stakes are expected to be raised, and MR. MONK’S LAST CASE certainly raises them.

If you noted the stockpiled pills and immediately thought: ‘Oh, Monk is contemplating suicide.’ then give yourself a pat on your back. There’s also a scene very early out of the gate where Monk longingly stares out of a high-rise window at the sidewalk below, and his fingers inch close to the window clasp. Also, he’s literally counting down the days on his paper calendar to a day with the name ‘Trudy’.

Solving Trudy’s murder didn’t bring Adrian the solace he had hoped for. Instead, coming out the other side he felt unmoored, unnecessary, a ship without a sail, and in his mind the only solution is to join Trudy in his idea of the afterlife. Dark? Sure. Too dark for MONK? Not at all as it feels organic to the character. Post-Trudy, Monk is a man who is never content, driven to placate himself but never finding peace.

“Poison in the very air we breathe.

Do you know what’s in the water we drink? Well, I do and it’s amazing.”

While Adrian Monk certainly shares DNA with a number of other murder mystery/detective fiction protagonists — MR. MONK’S LAST CASE has a number of blatant riffs, especially a very not-so-subtle insertion of an adoptable dog named ‘Watson’ — he mirrors Agatha Christie’s fastidious and fussy Belgian ex-policeman-turned-private-detective Poirot more than others.

Putting aside recent adaptations of Poirot mysteries, Hercules Poirot is an overly neat and tidy man, a man who is very proud of his perfectly coiffed mustache, of his immaculately shined shoes, of the fabric that lines his coat. Like Monk, Poirot becomes very agitated when anything disrupts his sense of order, be it mussing his attire or imperfectly sized eggs.

Also, like Monk, Poirot has an bit of an ego, is very aware of his talents and — as he himself puts it — his ‘little grey cells’, and is steadfastly stuck in his own ways. However, Monk and Poirot couldn’t differ more about their deduction techniques:

Monk’s technique is in the Holmes-ian mould in that he pieces together the murders utilizing precision knowledge of items and dates and scuffs and cigarette ash which inevitably result in comedic moments where Monk is disgusted by having to get down and dirty and then he throws a childish fit.

Nonetheless, Poirot is in every which way a Christie protagonist. While she was a relentless researcher and certainly knew of many ways to physically enable someone to kill someone, she was always more interested in the circumstances, the emotions and motivations and flawed humanity that drove one to commit such an act. While, yes, Poirot does ask suspects to detail their time and place around the murder, it’s not just the time and place he’s making note of, but the words and body language in-between those bullet points.

Like Arthur Conan Doyle’s frustration with how wildly popular his Sherlock Holmes creation had become, after having published far more Poirot novels than she thought she ever would she found herself tiring of the character. However, like Doyle, she came to the realization that for as long as she lived, Poirot would live alongside her.

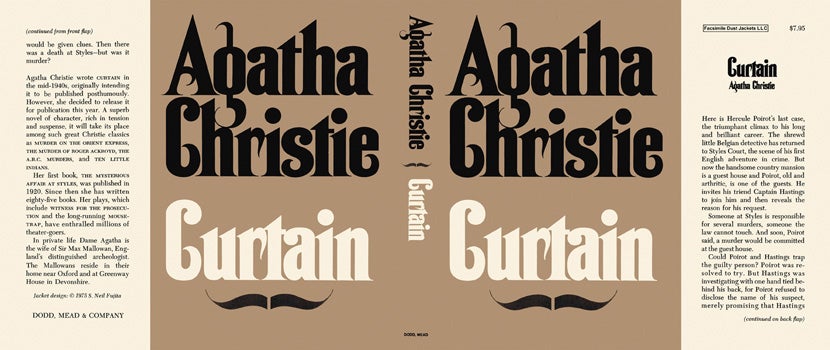

To cope with this, she did the next best thing. In the midst of WWII she penned Poirot’s final novel, CURTAIN: POIROT’S LAST CASE. While it starts like so many other Poirot novels — countryside inn, an ensemble of suspects, unexplained deaths — the circumstances are different this time around. Poirot and his affable sidekick Hastings are older. Times are changing. The world is different. The old guard is ailing, reduced to a number of medications to keep the heart beating. Tried-and-true techniques no longer guarantee the same results.

Part of Christie’s impetus was to ensure readers would receive proper closure regarding Poirot’s life and contributions, as it was also written with bombs falling around her and she was very unsure about the future.

Upon completion of CURTAIN, Christie locked the manuscript in a bank vault and continued to pen Poirot adventures, the last of which was ELEPHANTS CAN REMEMBER, published in 1972.

After penning the Tommy and Tuppence mystery POSTERN OF FATE in 1973, Christie knew that would be her last work so she unfurled CURTAIN and it was published in September of 1975. She lived to see the world react to Poirot’s literal end, but passed shortly after on January 12th, 1976.

It’s on record that Christie was a rather secretive person. Her ‘lost 11 days’ where she just up and vanished from her home and family, leaving behind numerous oddities that were construed as ‘clues’, including three envelopes handed out to staff only to be opened upon her death has the grist of a private joke. She was later found residing at a spa and she claimed to have no memory of the past 11 days.

What occurred between those 11 days, as well as the reasoning for leaving in the first place, has been the source of endless speculation, including several films and a Doctor Who episode.

“People think I’m crazy, ‘cause I worry all the time.

If you paid attention you’d be worried too.”

A brief aside: It’s been widely speculated that Christie was suffering from Alzeimers late in life. If you read her novels as they were published you can see her prose turn, leaning more into terse bouts of dialogue, characters often repeating or even contradicting themselves in non-writerly ways. Certain narrative twists don’t land or even make much sense. Hell, even the title of her last Poirot novel — ELEPHANTS CAN REMEMBER — seems to underscore that she was aware of her ailments.

The upside of this is that CURTAIN, a novel Christie wrote thirty years prior, a novel so rich and complex, a novel that reckons with one’s worth and ability and aging and expectations, reads thirty years later like nothing she has published in decades, but also reads like everything she’s wanted to put into words for so, so very long.

(I swear this is Eddie Campbell’s work! I wish I would have asked him when I met him!)

CURTAIN closes with Poirot murdering his suspect, despite the fact that he has no tangible evidence to link him to the five murders he’s investigating. Then, before bed, Poirot intentionally neglects his heart pills and he passes away in his sleep due to a heart attack. He dies torn between his actions to dole out justice, but also with the knowledge that he has enacted justice but can no longer be trusted to do so. He is tired; so tired.

He pens all of this to his sidekick Hastings, who receives Poirot’s scribed ‘drawing room speech’ several months after Poirot has been buried. Envelopes beget envelopes.

“And last of all, the pistol shot. My one weakness. I should, I am aware, have shot him through the temple. I could not bring myself to produce an effect so lopsided, so haphazard. No, I shot him symmetrically, in the exact center of the forehead…”

Poirot, CURTAIN, in a letter he penned for Hastings. [pg. 222]

MR. MONK’S LAST CASE leans heavily on all of the above, from the formal queasiness of asymmetry to feeling adrift from modern society, seeing one’s self as abnormal, the desire to kill one’s self to quell the madness around you, to be the sole person who can instill order no matter the cost, to hope for some kind of peace and solace that you’ve known in the past, to put a name and a date on it, to send envelopes containing words hedging around what all of this means, why one needed to see this through to the very bitter end…

“You better pay attention or else this world we love so much might just kill you.

(I could be wrong now, but I don’t think so!)”

I can’t say for sure that MR. MONK’S LAST CASE used Christie’s CURTAIN as an influence, a template, and — or — a springboard, but the pieces fit in a way that suits both protagonists, as well as for the viewers who are mystery nerds.

Despite having penned hundreds of words above about how MONK pays tribute to the detective fiction of the past, the show itself never calls attention to it or makes it the centerpiece of a scene. In other words, you don’t have to have read every Christie mystery or every Hammett potboiler in order to enjoy MONK. It’s a series that stands on its own two legs, while also acknowledging works that have inspired those willing the show into existence.

I should know. I started watching MONK a few seasons into its run and was smitten, despite having never glommed onto detective fiction in the past. I had barely read any of Doyle’s Sherlock tales, the only Christie works I saw were adaptations aired on MASTERPIECE THEATRE, which I mostly watched for the Edward Gorey animated opening sequence. I was into noir, but mostly for the moral ambiguity and the misfit characters and the grime and nihilism.

“‘Cause there’s a jungle out there.

It’s a jungle out there.”

Was MONK cozy? Sure. However, that general sense of melancholy, of feeling like you were a burr on society but also that society was a personal burr for you resonated deeply. Monk, the character, the persona, was one of a damaged individual just trying to get by. While he thought highly of himself, the world around him literally suffocated him. It may sound like a minor character tweak, but for the time — hell, even now — it’s far headier than the usual ‘oh I’m just a drunk with mommy/daddy issues but I’m also brilliant’.

MR. MONK’S LAST CASE is not just a shadow of CURTAIN. After all, this is a proper film — albeit made-for-streaming and all of the baggage that entails — and fills up two hours (with commercial breaks, naturally). Every facet of the show is dialed up to 11, including explosions, manner of deaths, almost all of the gang is back together and hell, even the number of exterior shots instead of bland offices and over-utilized Warner Bros. lot buildings have increased! They’re playing with a far larger budget than pretty much any TV-centric detective fiction fan is familiar with.

Also, simply because of Adrian’s germaphobic nature, the show handles COVID and the collective lockdown and repercussions far better than just about any other mainstream media work I can think of. Fittingly, the populace’s embrace of safety and awareness of infectious issues only serves to depress Monk further.

MR. MONK’S LAST CASE looks great: it no longer has its odd vaseline-ish patina, drones have been deployed, and the editing pushes and pulls where and when it should. The suspect? Well, let’s just say I wish the real-life counterpart faced the same sort of justice.

MONK was a certain type of show that is sadly going extinct; a crowd-pleaser of a collective effort that knew how to entertain, but also indulged itself in substantial and thoughtful riffs. It was show the whole family could watch, but each member would delight in vastly different facets of an episode.

MR. MONK’S LAST CASE manages to return to that form, to toe that line: it’s funny, it’s quippy, it’s smart, it pays homage to the past, it has a lot of spectacle, it explores the interiority of its namesake, it has a great villain, it’s not copaganda — I could go on and on.

Yes, MR. MONK’S LAST CASE is more open-ended than CURTAIN. However, I do hope it is how we leave him: in a better state than when we first met him.

“Eh bien.”

Hercule Poirot

“It’s a gift… and a curse.”

Adrian Monk

Addendum

Yes, I know. MONK has so many quotable moments, so why, why?! did I choose to only quote the Randy Newman song that serves as the title sequence, and wasn’t even part of MONK’s first season? ‘It’s a Jungle Out There’ is that succinct and, despite the fact that it was a song that pre-dates MONK, it perfectly encapsulates the show. That’s why. Best of luck getting that earworm outta your head now!